1968 protests

| The neutrality of this article is disputed. Please see the discussion on the talk page. |

In Spring 1968, the Morningside Heights campus was rocked by a series of protests, much like those taking place across the country and world. These remain the largest and most legendary protests in university history.

At Columbia, the events were ostensibly triggered by the planned construction of a gymnasium in Morningside Park following decades of neighborhood neglect on the part of the university. Other issues, such as the university's entanglements with the US government and the Vietnam War, played a contributing role.

The protests resulted in a student strike, the occupation of various campus buildings by radical student protesters over the course of a week in late April, and the division of the Columbia student body these actions caused. They came to a violent end when University President Grayson Kirk called in the NYPD to eject the protesters.

Aftershocks continued to disrupt university life for the remainder of the semester, and set the precedent for future protests on campus. The university did not recover from the financial and psychological fallout from the 1968 protests for decades.

Contents

Background

Expansion and middle-class flight

By the 1930s, Morningside Heights was fully developed. A surrounding middle-class community, not just of students, promised ensure Columbia's long-term stability. An intellectual community had risen alongside intellectual institutions.

The first expansion of the Moningside campus came in 1905, when the universide pushed southward to 114th Street. In 1906, it announced plans for a 55,000-seat football stadium in Riverside Park on the Hudson River at 116th Street, but the depression made it virtually impossible to raise the necessary funds for construction. The fact that football was banned in 1905 (and did not return to Columbia till 1915), ostensibly for "rowdiness", might also have something to do with it. At the same time, the university was growing and desired to secure housing for its students and faculty. In 1919 and 1920, it took over its first apartments on Claremont Avenue. It did so by waiting for the leases of existing tenants to expire and bought them out until it had acquired entire buildings.

After decades of development, the Great Depression completely stopped construction in the neighborhood. As the aftermath of World War II paved the way for Levittowns, the middle-class relocated to the sprawling suburbs. For Columbia, this meant that the intellectual community that was to preserve the neighborhood's desirability was free to leave. The great middle-class flight brought in a new community, unfamiliar to the neighboring intellectual institutions.

The postwar Morningside Heights was designed by frightful landlords that chopped up apartment complexes into smaller units that could be charged at a much lower monthly value. These, along with single room occupancy hotels (SROs) became the postwar Morningside Heights housing market. The neighborhood was no longer uniformly intellectual and middle-class, but a diverse mix of poorer African American and Puerto Rican families. Rather than welcoming the new neighbors, Columbia, believing its survival was in jeopardy, distanced itself completely (SOURCE?).

Morningside Heights Inc. and growing community tensions

Columbia and its neighboring intellectual institutions banded together and created an organization called Morningside Heights, Inc. in 1947 to stop white-flight and the growth of Harlem. Columbia believed the only way it could continue meant taking back the neighborhood. During the 1960s, the university purchased more than one hundred buildings in the area, mostly SROs, in an effort to save the university. White it worked, it merely escalated tensions that were set to climax in the midst of similar national struggles by the decade's close.

When a local resident asked by The New York Times what she thought of Columbia's takeover of buildings throughout the Morningside Heights neighborhood, she replied, "Sure we fear Columbia. After all what is it to us -- a place where our children can never hope to go to school, a place that may be our landlord one day, a place that may force us to move." The Cox Commission Report, published in the aftermath of the protests, revealed that in the early part of the decade, Columbia missed its chance to "use its resources in medicine, psychology, and the social sciences, to rehabilite the prostitutes, drug addicts, and other derelicts in SRO buildings, instead of buying them in an effort to 'clean up' the vicinity." At any rate, Columbia continued to expand -- to the east, it built a new law school building and a public policy school between Amsterdam Avenue and Morningside Drive, the institutional barrier protecting Morningside Heights from what had loosely devolved into the ghetto of Harlem.

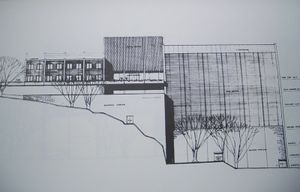

A gym in the park

Separating the intellectual world of Morningside Heights from the slums are 159 stairs that empty out into what was once one of the most blighted green spaces in all of New York: Morningside Park. With its finances back in order and a $2 million fund raising drive underway, the university again set its sights on expansion. In 1960, it announced plans to build a gymnasium in Morningside Park. Such a project would be the first of its kind: a large private institution was to take over public park space for its own interests.

The gymnasium was instantly met with criticism, but not for the reasons that would lead to the eventual building point of the latter sixties. In February of 1968, just as construction was finally to commence, twelve were arrested at the site for attempting to halt the bulldozers from entrance to the park. Protesters argued that the gym would desecrate the work of Frederick Law Olmsted, designer of the park (and also of Central Park). In the early sixties, however, reaction from the community to the proposed gym was generally positive. A Columbia Spectator poll released in November of 1967 showed that half of those that knew of the gym supported it. After all, Columbia had already been using the park for much of its outdoor athletics, for over a decade, and subsequently provided organized sports for the diverse community youth. In an editorial appearing in The New York Times in August of 1961 entitled, "Helping Morningside," the newspaper argued that "Morningside Park is one of the all-too-many 'danger spots' among our parks... [t]he character of the entire park could be helped by this gymnasium to be used in all seasons... Columbia University will develop this project in the spirit of neighborhood betterment." Unfortunately for Columbia, the city was still a decade away from routinely farming out public parks to private entities with the hope of cleaning them up for the public good. Time was not on Columbia's side, and the revolutionary mobilization of anti-institutionalism was to clash with what otherwise seemed like Columbia's giving back to the slums adjacent to Morningside Park

There were a number of problems associated with Columbia’s planned gymnasium. The first came in the form of funding. The university had to break ground by August 29, 1967 (and complete it within five years) or the project would be stopped by the city. In turn, the university embarked on a fundraising campaign to see the construction through. Initially, the project was to cost $6 million, but it eventually boomed to $13 million. This made it harder for the university to raise the money necessary to build the project in a timely fashion.

Opposition to the park was mounting from Parks Commissioner Tom Hoving, growing community tension, and the advancement the civil rights movement. Historian Vincent Cannato, in his biography of Mayor John Lindsay, noted that "[t]he university calculated that 88 percent of the building would be reserved for the university while only 12 percent was set aside for the community." Furthermore, the gym would have two separate entrances: one for students at the top, facing the main campus, and one for members of the community, in the back, and at the bottom. Parks Commissioner Hoving strongly opposed the arrangement and calling it "highly irregular."

Some politicians took the plans to their own advantage and established the false belief that Columbia "owns half of Harlem." Louis and Mary Lusky, in their report entitled "Columbia 1968: The Wound Unhealed" wrote that "[t]heir political leaders, sensing a chance to win something extra for their constituents, began to be heard." With the growing tensions of the sixties, it was beginning to look more and more like Columbia had lost its chance to build on Morningside Park; in the end, it was a combination of the totalitarian-like university administration structure coupled with the rise of student activism that eventually brought the gym construction to a bloody halt.

Students, administrators, and the sixties

In the early sixties, a strong lack of communication existed between students and administrators. Students were expected to comply with the seemingly totalitarian behavior of the prestigious university. The rise of sixties activism sought to break this barrier. The earliest great campus movement, known as the Free Speech Movement (involving 800 students), took place in 1964 on the campus of Berkeley. At Columbia, two radical organizations had emerged to take on the university administration. The first was the Students for a Democratic Society (or SDS), led by Mark Rudd. Whereas SDS embodied middle- and upper- class outrage, the Student Afro-American Society (SAS) arose to specifically tackle civil rights. Immediately, a divide existed between the two groups just on the basis of cause. However, like a microcosm of larger sixties activism, the convergence of the two produced enormous results.

The late sixties was also marked by the Vietnam War, and perhaps hit college students the hardest as their peers were routinely sent to battle a war that was highly unpopular on campuses. Columbia's then President Grayson Kirk sat on the board and executive committee at the Institute of Defense Analysis (IDA) and then Columbia Trustee and Lockheed and CBS board member William A.M. Burden was also the chairman of IDA's executive committee. Both Kirk and Burden recruited and recommeneded university professors for IDA's Jason Division, which developed weapons technology that the Pentagon utilized to prolong its war in Indochina, such as the automated electronic battlefield weapons technology (keeping in mind that Columbia's Manhattan Project of the 1920s led to the atomic bombs dropped over Japan to end World War II). Students felt that Kirk had failed to reveal that Columbia had been an institutional member of IDA since December 1959--prior to Columbia SDS discovering in March 1967 that Columbia, indeed, was an institutional member of the Pentagon's IDA weapons research think-tank. Furthermore, Columbia had submitted class rank information to the Selective Service System to be used in selecting draft deferments until the spring of 1967. When Mark Rudd brought his petition of 1,500 signatures from members of the Columbia community to President Kirk's office urging a withdrawal in IDA, he received no reply. It was the combination of these issues that contributed to the uprsising that would follow at Columbia.

Events of Spring 1968

The IDA Six

When a student was asked to indicate which issue he found most troubling with Columbia at the time of the eventual uprising, he replied, "I have to tell you that if a protester argued about the paint color on the building not being democratic, I probably would have protested that too. What I'm trying to say is that I was desperately seeking issues to vent my frustration and disempowerment." Had Columbia built a gymnasium ten years earlier during the historically conservative fifties, it would have just escaped this student animosity. Instead, it was the sixties and anything that touched a larger issue would be placed under the microscope by radical groups demanding institutional accountability.

When he was unable to communicate respectfully with President Kirk, Mark Rudd issued a letter declaring that "[y]ou call for order and respect for authority; we call for justice, freedom, and socialism... [u]p against the wall, motherfucker, this is a stick-up." Rudd and five others (who would come to be known as the "IDA Six") were threatened with disciplinary probation after participating in an indoor "anti-IDA" protest inside Low Library on March 27, 1968, which demanded that the Columbia Administration resign its institutional membership in IDA. One month later, on April 22, the IDA Six met with a dean and were placed on probation by the university. The following day, SDS held a rally in support of the IDA Six. They marched into President Kirk's office demanding an open hearing. SDS also took the opportunity to mobilize SAS by acting out against the gymnasium. SAS now had the radical SDS behind them.

The occupations

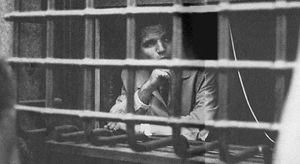

While the doors to Low Library had been locked, and counter-protesters from the Majority Coalition (mostly clean-shaven athletes with slick hair) blocking the doors, the protest shifted to Morningside Park, where protesters planned to rip down the chain link fence surrounding the construction site of the gym. Subsequently, some protestors moved to Hamilton Hall and imprisoned Henry Coleman, Dean of Columbia College, in his own office.

While in Hamilton, the students organized a "Strike Coordinating Committee" and established six demands: amnesty for the protesters facing probation, repeal of the rule against indoor demonstration, ceasing construction of the gymnasium, disaffiliation with the IDA, and an effort from the university to push for charges to be dropped on anyone who interfered with gymnasium construction.

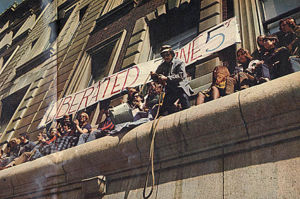

In the next few hours, the Hamilton sit-in would become comprised exclusively of black students. Black students not only protested the gymnasium, but they also rose up against Columbia's lack of African-American students on campus, along with general discrimination. The gym was largely a secondary complaint. By the next day, they demanded the white students leave them Hamilton in order to express their own, independent concerns. The protesting whites complied. Later, neighborhood activists from Harlem would surround the university, in solidarity with the Hamilton strikers, and nationally known black activist leaders would visit the site. Hamilton was renamed "Malcolm X Liberation College."

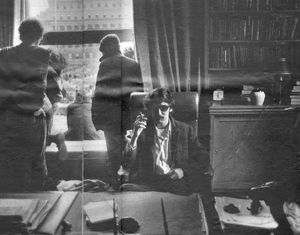

The approximately 100 white students forced out of Hamilton broke into Low Library and settled in the offices of President Kirk and Vice President David Truman, all within the first 18 hours of the strike. By April 25, students had taken over five buildings at Columbia, including Fayerweather. Avery Hall was loosely occupied by sympathetic School of Architecture students, and Mathematics Hall was taken by the most radical students.

The faculty reacted in various different ways. Some sided with the administration, which had already called in the police to storm Low before hearing of the loss of Mathematics. Eventually, these faculty tried to blockade Low from incoming protesters on their own - to no avail. Others formed the Ad Hoc Faculty Group to try to broker negotiations between the strikers and the admiistration.

While all this was happening, some professors even continued to hold classes, some just outside the occupied buildings where they normally taught.

In Low Library, many students were occupied reading documents in President Kirk's office, while not consuming his sherry and cigars. Elsewhere, occupying students busied themselves with long political debates. A hippie wedding was staged in Fayerweather.

Neighborhood sympathizers catapulted food into the occupied buildings, while members of the counter-protesting Majority Coalition attempted to block these deliveries, and placed Low under siege. The Majority Coalition also tried to retake Fayerweather, but were unsuccessful.

Access to the occupied buildings by campus journalists is legendary. Many still wonder how reporters from the Spec and WKCR were able to get scoops on events inside Low Library that national networks were missing out on. One theory is that they had discovered a secret tunnel linking Butler to Low, but the existence of this tunnel has long been denied, and efforts to locate it have failed.

The attempts of the Ad Hoc Faculty Group to broker a compromise failed to bear any fruit, nor did promises from the administration (including the pledge to end construction of the gym). In desperation, the AHFG turned to the major of New York, John Lindsay, for help. It was too late, however: Kirk had already announced that the NYPD were to be called to break up the protests.

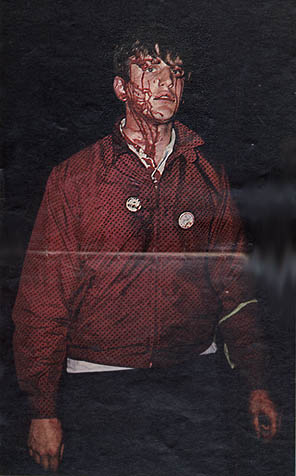

The police bust began shortly after 2am on April 30. Police stormed buildings either in frontal assaults or secretly, via the tunnels. In some cases, they battled lines of faculty and students who had not agreed with the occupations but were livid over the use of police power on campus. By all accounts, violence was the rule on all sides. The police were not discriminate. Over 700 students were arrested, and over 150, many not even protest participants, but passive spectators, were injured by police violence.

The next day, disorder reigned on campus, and students attacked police officers dispatched to keep order.[1] Classes were almost all immediately suspended, and would continue to be for nearly a week.

Aftermath of the protests and criticisms

In the end, many of the students' demands were met. Construction of the gym had been suspended. Students gained greater communication with the administration. However, it took decades for the university to restore its image. Alumni donations were down following 1968 and applications for admission had dropped by 20 percent in the next cycle. Perhaps the biggest crime to come out of the vents at Columbia was suffered at the hands of the surrounding neighborhood, as without a gym, Morningside Park had little changed. Not only did it remain the blighted institutional barrier separating the intellect from the ghetto, but it could also be blamed as part of the reasoning behind the institutional collapse of a prestigious university.

In 1972, Columbia quietly began construction of a gym built within its own private gates at a northern part of the campus known as The Grove (ironically, first suggested as a site for a gym in 1892 during the university's initial construction in Morningside Heights). Construction of what was to be called Levien Gymnasium was met with no opposition. It remains quite small compared to what could have been. For the university, it has served as a detriment to athletics recruitment and has contributed to a subsequent lackluster athletics program. Nevertheless, the university was seemingly forced in this direction. It was eager for a gymnasium, but unable to wait for the tensions of the sixties to fade. Levien Gymnasium was completed in 1974 and provided no facilities for the neighboring community. With its opening, the university had done everything in its power to cleanse itself of the 1968 protests.

Since 1968, Columbia has been forced to develop mainly within its own gates. In doing so, the university has been unable to greatly expand at a time in which other academic institutions have done so and continue to do so to attract more students, a better faculty, and generate greater research. Similar concerns have arisen in what is known as the Manhattanville controversy, referring to President Bollinger's use of eminent domain to expand Columbia's campus into the Manhattanville neighborhood.

Outside media coverage

September 30 cover story in Newsweek: "Rebels on the Campus: Confrontation at Columbia"

Notable participants

Admins

- Henry Coleman, Dean of Columbia College taken hostage

- Grayson Kirk, University President

- David Truman, Provost

Faculty

Mediators in the Ad Hoc Faculty Group:

- William Theodore de Bary

- Daniel Bell

- Robert Fogelson

- David Rothman

- Allan Silver

- Immanuel Wallerstein

Supported students:

Taught through it:

Protesters

- Paul Auster, later novelist

- Ted Gold

- Mark Rudd

- David Shapiro

Other

- William Barr, future US Attorney General, member of the counterprotest Majority Coalition

Books

- The Ungovernable City: John Lindsay and His Struggle to Save New York (chapter 7) by Vincent Cannato

- Up Against the Ivy Wall: A History of the Columbia Crisis by Jerry L. Avorn

- The Battle For Morningside Heights by Roger Kahn

- The Strawberry Statement by James Simon Kunen

References

External links

- Columbia library online exhibition

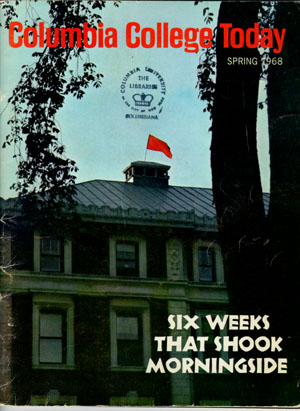

- Full PDF of the Spring 1968 Columbia College Today

- Recollections of police violence by Robert McFadden, Times reporter

- Double irony - protester becomes judge, his campus interview interrupted by campus police - NY Times

- Spec Web Feature on the 40th anniversairy

- Digital copy of Columbia College Today's Spring 1968 issue

- Who Rules Columbia? Original 1968 Strike Edition

- Sundial: Columbia SDS Memories

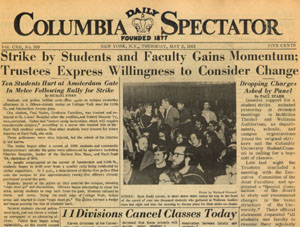

- Crisis at Columbia: Spectator coverage April 24 - May 8, 1968